One of the most comprehensive assessments was conducted as part of the Six City study. The association of respiratory symptoms with indoor nitrogen dioxide level was examined in more than 1500 children , who were followed up for one year. About half of the children lived in homes with a major source . Household annual average levels were determined based on summer and winter measurements made in three household locations, and were 16.1 μg/m3 for homes without a source and 44.2 μg/m3 for homes with a source. Household particulate matter (PM 2.5) was also measured in this study and included as a covariate in the final analysis.

Density Of Air At Stp The observed association of incidence of symptoms with both the presence of a gas stove and with increasing indoor nitrogen dioxide level persisted after adjustment for the indoor particle level. In this study, no consistent association of lung function with source or measured nitrogen dioxide was observed. Cross-sectional studies were conducted in the Netherlands, where there was concern over the combustion products produced by gas water heaters or geysers. The average nitrogen dioxide concentration over a period of several days may exceed 150 μg/m3 when unvented gas stoves are used . On the other hand, wood-burning appliances were not related to elevated nitrogen dioxide concentrations in a Canadian study carried out in 49 houses .

While most studies of indoor air pollutant exposures from biomass burning in developing countries have focused on airborne particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide levels can also be elevated. In a study in Ethiopia where wood, crop residues and animal dung were the main household fuels, the mean 24-hour concentration of nitrogen dioxide was 97 μg/m3. A study in rural, urban and roadside locations in Agra, India showed the dominance of outdoor sources on elevated indoor nitrogen dioxide concentrations (indoors 255 ± 146 ppb; outdoors 460 ± 225 ppb) . These observations that children with asthma have worse symptoms if exposed to higher levels of indoor nitrogen dioxide suggest that their removal from exposure should lead to amelioration of their symptoms.

However, few interventional studies have been reported. In recognition that classroom levels of nitrogen dioxide are an important source of exposure, an intervention study was conducted in Australia. Researchers assessed the effect of changing from unflued gas heaters in school classrooms to flued gas heaters or electric heaters . Almost 200 asthmatic children in 10 control schools, 4 schools that had changed to flued gas heaters and 4 schools that had changed to electric heaters were followed for a period of 12 weeks.

Following the intervention, the mean rate of symptoms of difficulty breathing during the day and at night, chest tightness and asthma attacks during the day was lower in children attending intervention schools. No change in lung function parameters was observed. Six-hourly average classroom levels of nitrogen dioxide ranged from 13.2–71.4 μg/m3 to 22.5–218.1 μg/m3 during the period of follow-up.

The association of respiratory symptoms with gas for cooking may be modified by levels of outdoor nitrogen dioxide. This was examined in a small study in Hong Kong SAR, where cooking with gas is almost universal. Children living in two contrasting areas were examined . In an area with relatively low background pollution (nitrogen dioxide annual mean 45 μg/m3), current doctor-diagnosed "respiratory illness" was more common in children living in homes that cooked most frequently with gas.

Experimental animal work on the health effects, and mechanisms thereof, of nitrogen dioxide has not focused on indoor sources or exposure patterns of the pollutant . As such, in addition to newly published work, the studies reviewed in this section include those described in WHO's latest guidelines for ambient nitrogen dioxide . Acute exposures to low (75–1880 μg/m3; 0.04–1.0 ppm) levels of nitrogen dioxide have rarely been observed to cause effects in animals.

Subchronic and chronic exposures to low levels, however, cause a variety of effects, including alterations to lung metabolism, structure and function, inflammation and increased susceptibility to pulmonary infections. Emphysema-like changes , features characteristic of human COPD , generation of an atopic immune response and airway hyperresponsiveness have been reported only at high (15 040– μg/m3; 8–25 ppm) nitrogen dioxide concentrations. It is apparent from both in vitro and animal toxicology studies which toxic effects of nitrogen dioxide might occur in humans.

To overcome this problem, one study in Sweden compared respiratory symptoms in children who played ice hockey in ice arenas with propane-fuelled and electric resurfacing machines . Some 1500 children aged between 10 and 16 years who had played ice hockey in the previous three years and had trained in one of 15 indoor ice arenas were identified. The remaining six arenas used electric resurfacing and the equivalent indoor nitrogen dioxide levels were 9 μg/m3 (4–31 μg/m3). The authors then looked at children attending the propane arenas only.

They considered exposure as "high nitrogen dioxide" if levels were above the median and low if below the median. The vast majority of the children (over 80%) had played ice hockey for more than three years in these arenas. Significant association of various respiratory symptoms or lung function indices with nitrogen dioxide measured indoors or as personal exposure in all identified epidemiological studies of asthmatics (23,26,160– 162,164,165,168,191,268).

Lowest measured levels were ca. Given the density of dry air at STP, let's calculate its average molecular weight. So from the ideal gas equation pressure. Have some solar map is equal to the density times are constant times of temperature rearranging here at the molar mass is equal to D. It has been argued that the variations in the reported association of indoor nitrogen dioxide with respiratory health may be explained by failure to measure this co-pollutant .

The dearth of studies in which both have been measured has been identified as a gap in our understanding of the health effects of gas appliances . The association of exposure to gas appliances in infancy to later respiratory health was examined in Australia, where gas heaters are the main source of indoor combustion products. As part of the Tasmanian Infant Health Survey, the type of heating appliance in use in infancy was recorded and, at the age of seven years, information on respiratory symptoms was collected . There are many more studies on the association of health with the presence of gas appliances than with measured nitrogen dioxide and they are of varying quality. While cross-sectional studies are of interest in making a causal inference, greater weight would naturally be placed on those that are longitudinal in design. However, respiratory disease may occur in the absence of measurable change in lung function parameters.

We also searched for epidemiological studies on health effects of indoor gas combustion without measurements with the terms "air pollution, indoor", "gas" with "cooking" or "heating", and "respiratory tract diseases" or "lung function". Controlled exposure studies in humans have shown acute respiratory health effects of short-term exposures in healthy volunteers or those with mild preexisting lung disease. Mechanical failure of resurfacing machines in ice arenas leading to short-term, high-dose exposures demonstrates similar effects and suggests there may be long-term sequelae. Population-based studies have shown health effects of chronic indoor nitrogen dioxide exposure in infants, children and adults. Recent well-conducted epidemiological studies that have used measured indoor nitrogen dioxide levels support the occurrence of respiratory health effects at the level of the guideline.

In Hong Kong SAR, mothers of children taking part in a large study of respiratory health wore personal nitrogen dioxide badges for a 24-hour period . Personal nitrogen dioxide was higher in women if they cooked more frequently, but only among those who did not ventilate their kitchen by the use of an extractor fan. In users of LPG or kerosene, the mean personal 24-hour average exposure was 37.7 μg/m3 if the kitchen was ventilated during cooking and 41.7 μg/m3 if the kitchen was unventilated. There was no consistent association of personal nitrogen dioxide with frequency of cooking or presence of ventilation fans in the children living in these homes, probably reflecting their different time-activity patterns. Personal nitrogen dioxide was higher in women who cooked with LPG compared to those using piped gas. The Hasselblad meta-analysis.

In the early 1990s, Hasselblad et al. published a meta-analysis of the association of indoor nitrogen dioxide levels with respiratory illness in children . This report was one of the earliest examples of the use of meta-analysis for synthesizing evidence from studies of environmental hazards. Box 5.1 summarizes some of the key factors that influence indoor nitrogen dioxide levels and likely explain much of the variation reported in Table 5.1. Indoor levels of nitrogen dioxide are a function of both indoor and outdoor sources. Thus, high outdoor levels originating from local traffic or other combustion sources influence indoor levels. Annual mean concentrations in urban areas throughout the world are generally in the range of 20–90 μg/m3.

In the European Community Respiratory Health Survey covering 21 European cities, annual ambient nitrogen dioxide concentrations ranged from 4.9 μg/m3 in Reykjavik to 72 μg/m3 in Turin . The maximum hourly mean value may be several times higher than the annual mean. For example, a range of 179–688 μg/m3 nitrogen dioxide has been reported inside a car in a road tunnel during the rush hour .

A longitudinal study of indoor nitrogen dioxide levels and respiratory symptoms in inner city children with asthma. Personal nitrogen dioxide exposure was measured in 3–4-year-old children in Quebec City, Canada during the winter months and a dose-dependent association of exposure with asthma was reported. Only 6 of the 140 children lived in a home with a gas stove (mean personal exposure with gas stove 32.4 μg/m3; without gas stove 17.3 μg/m3).

The adjusted OR for case status with the highest level of exposure appears unrealistically high, with very wide confidence levels (24-hour mean of 28.2 μg/m3 compared to "a zero level"). The unmatched analysis OR was 19.9 (95% CI 4.75 –83.03) while the matched analysis OR was 10.55 (95% CI 3.48 –31.89) ; this was probably related to the small numbers of children in the risk group. Personal exposure to nitrogen dioxide was measured in children in Hong Kong SAR , where indoor sources are common. No association of exposure with symptoms was observed.

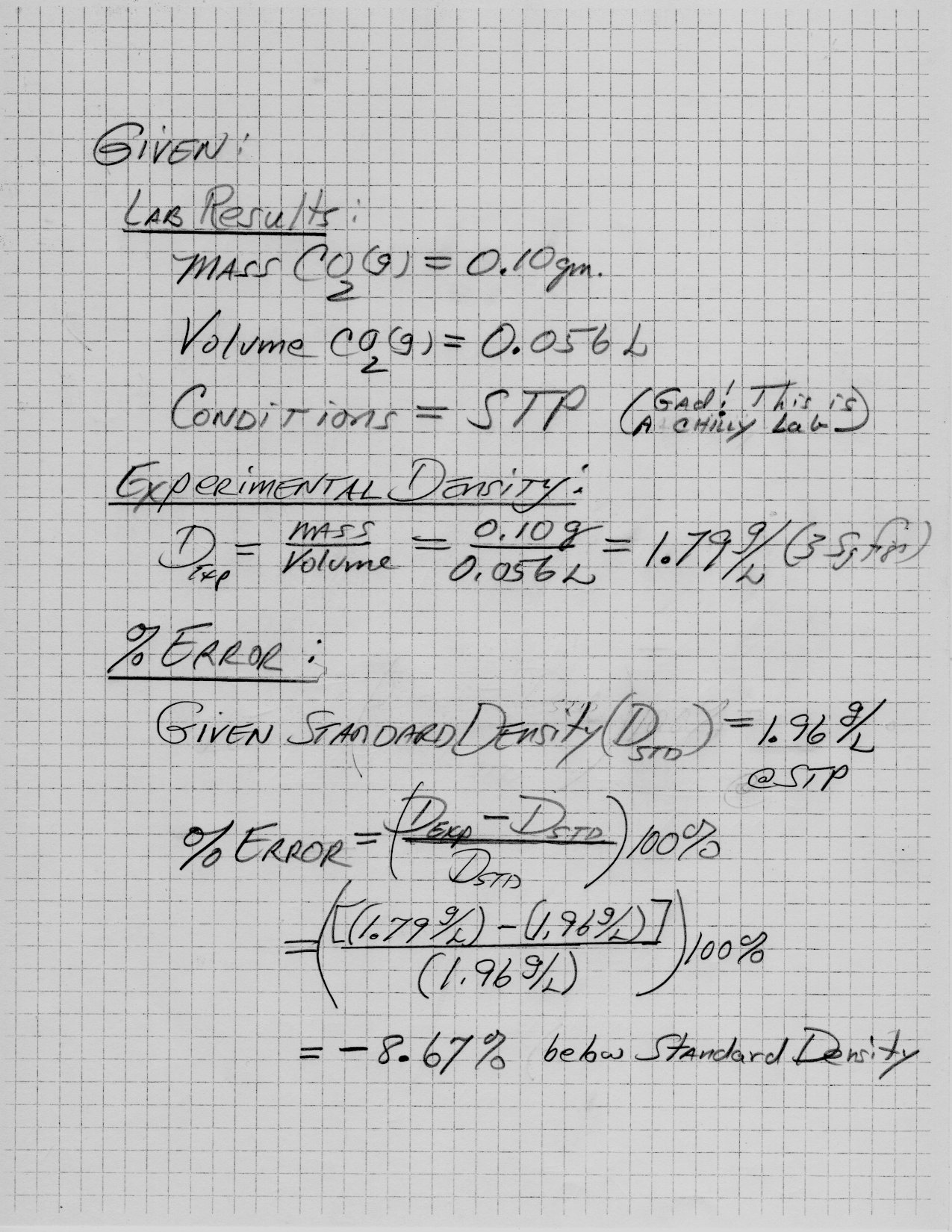

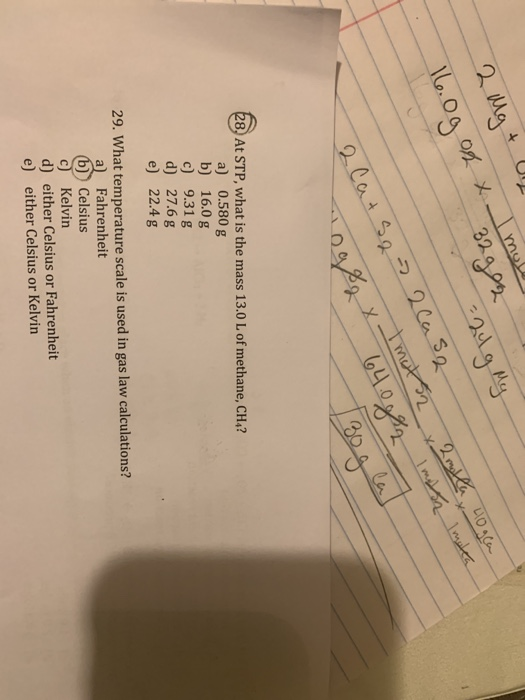

That has a molar mass of 40 grams per mole, and it makes up 0.93% of the air, which gives us 0.37 grams per mole of air. So if we add all of this together, we get 28.93 grams per one mole of air. So this is our answer for part A. And then in part B were asked to find the density of one mole of air at STP. So STP is standard temperature and pressure For SCP, the temperature is always to 73 K and the pressure is one a t.

The majority of epidemiological studies have examined populations with average indoor levels that can be considered representative of longer-term population exposures. Chronic health effects of exposure were also examined in Finland . Junior ice hockey players were asked to complete a questionnaire. Information on the weekly average nitrogen dioxide in the ice arenas in which they trained was collected (range 21–1176 μg/m3; mean 228 μg/m3). In comparison to the number of studies in children, there are relatively few studies that have reported associations of adult respiratory health with indoor nitrogen dioxide levels.

Review the epidemiological evidence for health effects of exposure to gas appliances in the home – a proxy marker for high exposure to indoor nitrogen dioxide. In another study, exposure to nitrogen dioxide over a lower concentration range (94–1880 μg/m3; 0.05–1.0 ppm) resulted in the antioxidant defences, uric acid and ascorbic acid being depleted in human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid . More recently, Olker et al. have shown that superoxide radical release is significantly impaired from BAL cells isolated from rats exposed to nitrogen dioxide ( μg/m3; 10 ppm) for 1, 3 or 20 days.

Indoor studies suggest that those using gas cookers, particularly in poorly ventilated spaces, can experience peak nitrogen dioxide exposures in excess of 500 μg/m3. Important factors that may increase indoor exposure are the use of unvented gas appliances, poor ventilation, proximity to major highways and the use of propane- and petrol-fuelled ice resurfacing machines in indoor ice arenas. Controlled exposure studies in humans assessing the health effects of short-term exposures have used well-standardized, objective methods for the assessment of health effects. In epidemiological studies, self- reported symptoms have been widely used as the health metric. These measurements are susceptible to over-reporting by those who perceive their exposure to be high. Although lung function measures provide more objective estimates of health status, inflammatory changes and symptoms may occur in the absence of lung function changes.

The association between exposure to common air pollutants, including nitrogen dioxide, and altered host immunity to respiratory viral infections has recently been reviewed . Two studies by Rose et al. exposed mice to nitrogen dioxide at 9400 μg/m3 for six hours per day for two days prior to infection with murine cytomegalovirus, followed by another four days of nitrogen dioxide. Enhanced susceptibility to infection was not found after exposure to 3100 or 1800 μg/m3 (2.5 or 1 ppm) nitrogen dioxide.

In addition to the direct release of nitrogen oxides, indoor combustion sources emit various co-pollutants including ultrafine particles, which are also produced during cooking . Secondary reactions, such as the production of nitrous acid from surface chemistry involving nitrogen dioxide, can contribute to indoor pollutant concentrations that directly affect health . Association of indoor nitrogen dioxide exposure with respiratory symptoms in children with asthma. Seasonal variability can be significant, owing to variations in source use (e.g. heaters and stoves) and seasonal fluctuations in air exchange rates. This variability results typically in higher indoor concentrations during winter months .

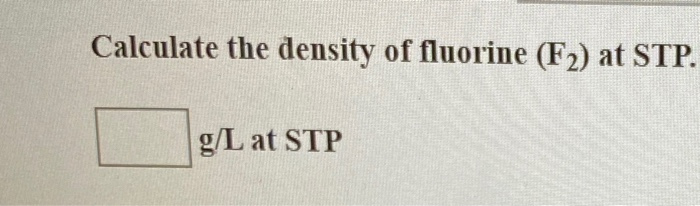

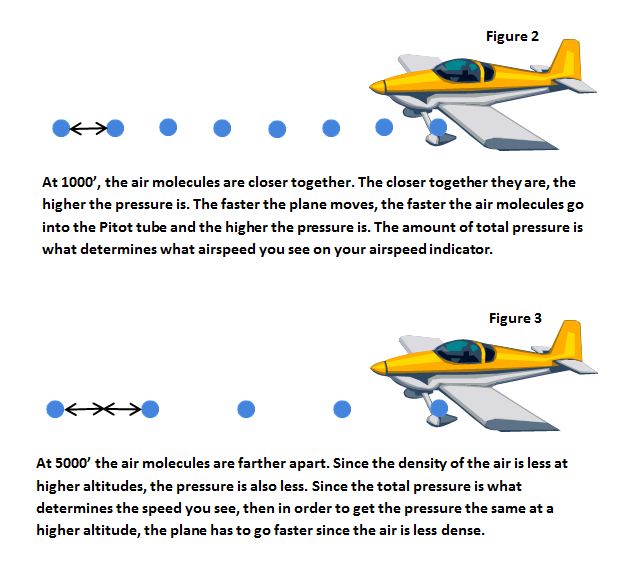

This variability, and its principal determinants, should be considered when extrapolating from exposure estimates determined using daily or weekly measurements to estimates of annual exposures. Since few studies have directly measured annual averages of indoor nitrogen dioxide concentrations, periodic measurements across seasons would be needed to construct representative estimates of long-term exposure. Standard temperature and pressure are a useful set of benchmark conditions to compare other properties of gases. At STP, gases have a volume of 22.4 L per mole. The ideal gas law can be used to determine densities of gases.

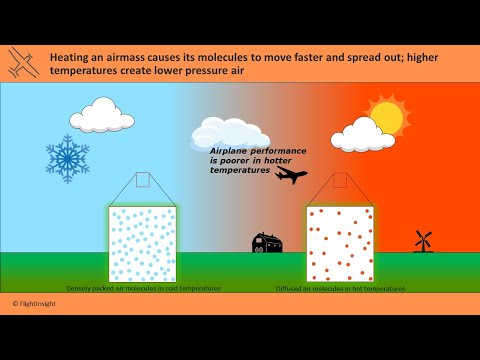

For any ideal gas, at a given temperature and pressure, the number of molecules is constant for a particular volume (see Avogadro's Law). So when water molecules are added to a given volume of air, the dry air molecules must decrease by the same number, to keep the pressure or temperature from increasing. Hence the mass per unit volume of the gas decreases. The gas constant is measure of the weight of the number of molecules of a gas. In the atmosphere around us we have air which is about 78% Nitrogen , about 21% Oxygen and about 1% other gases. Nitrogen has a molecular weight of 14 so a N2 molecule has a molecular weight of 28.

Oxygen has a molecular weight of 16 so an O2 molecule has a molecular weight of 32. Given the mixture of gases found in air the average molecular weight of air is around 29. Epidemiological studies conducted in several countries show that a proportion of homes and classrooms have indoor nitrogen dioxide levels exceeding the WHO ambient guidelines for outdoor air. Studies that have examined associations between respiratory symptoms and indoor measurements of or personal exposure to nitrogen dioxide. Indoor concentrations of nitrogen dioxide are also subject to geographical, seasonal and diurnal variations. Differences in the indoor concentrations in various countries are mainly attributable to differences in the type of fuel used for cooking and heating and the rate of fuel consumption.

While few studies have included repeated measurements of indoor nitrogen dioxide levels, it is known that within-home variability can be significant owing to the various contributing factors discussed above . Levy et al. studied nitrogen dioxide concentrations in homes in 18 cities in 15 countries, reporting two-day means ranging from 10 μg/m3 to 81 μg/m3 and personal exposures from 21 μg/m3 to 97 μg/m3. The use of a gas stove was found to be the dominant activity influencing indoor concentrations. Results showed also the importance of combustion space heaters to elevated nitrogen dioxide concentrations.

Road traffic is the principal outdoor source of nitrogen dioxide. The most important indoor sources include tobacco smoke and gas-, wood-, oil-, kerosene- and coal-burning appliances such as stoves, ovens, space and water heaters and fireplaces, particularly unflued or poorly maintained appliances. Outdoor nitrogen dioxide from natural and anthropogenic sources also influences indoor levels. Occupational exposures can be elevated in indoor spaces, including accidents with silage and in ice arenas with diesel- or propane-fuelled ice resurfacing machines and underground parking garages .

Overpay the density is equal to 1 to 9 to nine grams per liter. Our is our ideal gas constant 08 to 06 Leaders. Criminal Calvin temperature is standard temperature zero degrees Celsius or 2 73 kelvin. Standard pressure is one atmosphere pressure. Effects of exposure to gas cooking in childhood and adulthood on respiratory symptoms, allergic sensitisation and lung function in young British adults.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.